Flowing from that, an often unstated assumption of much political analysis is that movement takes places in the centre of the spectrum. To achieve political gains it follows one must persuade centre-right or centre-left voters to move a little in the opposite direction in order to make gains. This view of politics is central to much analysis of American politics, especially inside the Washington D.C. beltway, but it is being contested by an outsider.

|

| Rachel Bitecofer |

What made her reputation as a forecaster is that early on she accurately predicted the outcome of the 2018 elections for the U.S. House of Representatives. As the Politico item put it:

Bitecofer, a 42-year-old professor at Christopher Newport University in the Hampton Roads area of Virginia, was little known in the extremely online, extremely male-dominated world of political forecasting until November 2018. That’s when she nailed almost to the number the nature and size of the Democrats’ win in the House, even as other forecasters went wobbly in the race’s final days. Not only that, but she put out her forecast back in July, and then stuck by it while polling shifted throughout the summer and fall.Here is an example of conventional analysis from the period from the New York Times public opinion writer Nate Cohn about ten days before voting day:

Dozens of House races remain extremely close in the closing days of the midterms, according to New York Times Upshot/Siena College polls, making it easy to envision a Democratic blowout or a district-by-district battle for control that lasts for weeks of counting beyond the election.

The difference between the two outcomes will depend on whether enough Democratic candidates get over the top in the long list of Republican-leaning areas they’ve put into play. The Democratic gains in predominantly white, well-educated suburbs have stretched the Republican majority exceedingly thin. Fighting against this is partisan polarization, which could allow Republican incumbents to narrowly hold on to districts carried by the president.

The uncertainty isn’t just about hedging. It’s a reflection of the sheer number of highly competitive districts, and the limited data available about each one.Cohn was uncertain and could not decide where things were headed months after she made her accurate prediction. Bitecofer argues that her success is rooted in an appropriate appreciation of the phenomenon of "negative partisanship". In an article for the for the New Republic she begins by first articulating the perspective of Nancy Pelosi on the 2018 success.

On election night 2018, newly re-gaveled House Speaker Nancy Pelosi presided over a celebratory press conference after the Democratic Party’s recapture of a majority in the U.S. House of Representatives. At the center of the party’s success, Pelosi explained, was its “For the People”agenda—and particularly the party’s laser-focus on health care access and the protection of preexisting conditions in Obamacare. Adding a new spin on Tip O’Neill’s timeworn political adage “all politics is local,” Pelosi triumphantly declared “all politics is personal.” This pragmatic emphasis on basic economic safeguards, Pelosi argued, had powered a historic blue wave. Ultimately, Democrats managed to flip 40 Republican-held House seats, ousting 31 Republican incumbents in the process.By contrast argued Bitecofer:

...there was something very different about the 2018 cycle—and it’s something that the health care thesis fails to address. That something was voter turnout. After waning to historic lows in 2014, voter turnout in 2018 reached historic highs, smashing even the very high expectations set for the cycle in my own forecast. The 53.4 percent turnout in 2018 was closer to what we typically see in a presidential election than a midterm cycle. It dwarfed the 2014 cycle’s midterm turnout of 36.7 percent by nearly 17 points. And for all the talk of how central health care was that year, it was certainly not any more salient than it had been in the other elections since Obamacare was first enacted in 2010...

Indeed, if the health care policy debate should have been driving turnout in any major recent cycle, it was in the 2016 election, not 2018. The 2018 congressional battle over health care only came to pass, after all, because Trump ran hard on the pledge to “repeal and replace Obamacare,” and won....

So what, then, really drove the dramatic surge in voter turnout in 2018? It happened for one simple reason—or, rather, because of one simple man: Donald J. Trump. Trump’s surprise victory on election night 2016 set into motion conditions that all but guaranteed Democrats would take back control of the House of Representatives two years later, even as the GOP managed to hang on to a narrow majority in the Senate.

My forecasting model for the 2018 midterms predicted an enormous Democratic wave in the House, mostly by focusing on a dynamic known in political-science circles as negative partisanship. The idea behind negative partisanship is simple, harking back to Henry Adams’s definition of politics as the “organization of hatreds.” The determination to vote out the opposition—and the broader trend of acute polarization within the American political system—has altered virtually every facet of our political life. Negative partisanship is affecting the behavior of voters and reshaping the voting coalitions aligned behind each major party.

Negative partisanship is also the reason why the pending 2020 presidential and congressional cycle doesn’t call to mind charged modern ideological battles such as 1964 and 1972 so much as the fateful election of 1860, which ended up kicking off the Civil War....The U.S. Civil War that followed on the 1860 election (the last time the U.S. was so divided) is echoed in the distribution of political support among states today. The Republicans own most of the states of the old confederacy because they made a deliberate turn to the racist right in 1968 in a deal cut between Richard Nixon and South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond. Trump explicitly caters to the extreme right and the racial divide is a key force underpinning the partisan gap. The hyperpartisanship also explains the tenacity of Trump's support. Bitecofer in New Republic again:

We see this play out daily in the static polling on Trump’s approval numbers. These figures are virtually unresponsive to events, even to dramatic shifts in the political landscape such as Trump’s impeachment. We can also see this bedrock level of partisan attachment in election outcomes such as the special Senate election in Alabama in late 2017. In that contest, Roy Moore, the Republican nominee, faced credible accusations of child sexual abuse but still managed to accrue 48.3 percent of the state’s vote share. That outcome furnished a prime case study in polarization, with fully 91 percent of the state’s Republican electorate voting for Moore.Her overall approach makes sense to me and I think it has broad application. In the 2018 election there were two races that illustrate what happened. In the Tennessee Senate election that year the Democrats nominated a traditional southern 'moderate', Phil Bredesen, but in trying to straddle the middle of the road he did not win over Republicans and actually alienated some liberal voters. He ended up losing by eleven points. By contrast in Georgia the Democrats nominated Stacey Abrams for Governor, a black woman progressive, the first such candidate in the state's history. She lost by less than two points and likely would have won save for the cheating and vote suppression by the Republicans.

A mentor of Bitecofer, political scientist Alan Abramowits sees the current polarization like "a bitter sports rivalry, in which the parties hang together mainly out of sheer hatred of the other team, rather than a shared sense of purpose. Republicans might not love the president, but they absolutely loathe his Democratic adversaries. And it’s also true of Democrats, who might be consumed by their internal feuds over foreign policy and the proper role of government were it not for Trump."

Essentially Bitecofer took this insight and using voter files, polling, other demographic data and most importantly, data on voter turnout, mapped it across the United States, arguing "there are Democratic and Republican coalitions, the first made of people of color, college-educated whites and people in metropolitan areas; the second, mostly noncollege whites, with a smattering of religious-minded voters, financiers and people in business, largely in rural and exurban counties." It is who shows up on voting day that matters. Once you can figure that out, you can calculate the outcome.

Bitecofer does believe that the Democrats need strategies to drive turnout this year to assure success. One such is Biden's choice for Vice-President. Hilary Clinton chose Tim Kaine, a moderate designed to appeal to centrist Republicans, exactly the wrong choice. Bitecofer thinks Biden should choose a VP to drive turnout. He has already partly done that by saying he will select a woman. As the Politico article noted she believes:

For Democrats to win, they need to fire up Democratic-minded voters. The Blue Dogs (TC's note: moderate or right leaning Democrats) who tried to narrow the difference between themselves and Trump did worse, overall, than the Stacey Abramses and Beto O’Rourkes, whose progressive ideas and inspirational campaigns drove turnout in their own parties and brought them to the cusp of victory.She also thinks having a VP candidate that can appeal to the progressive wing of the party matters because "strategy, candidate quality, and especially candidate demographics can still matter on the margins and Democrats will roll into the fall general election with one clearly exploitable weakness: disaffection within the progressive base. The GOP will seek to exploit that weakness and Democrats would be wise to shore up every weak spot..."

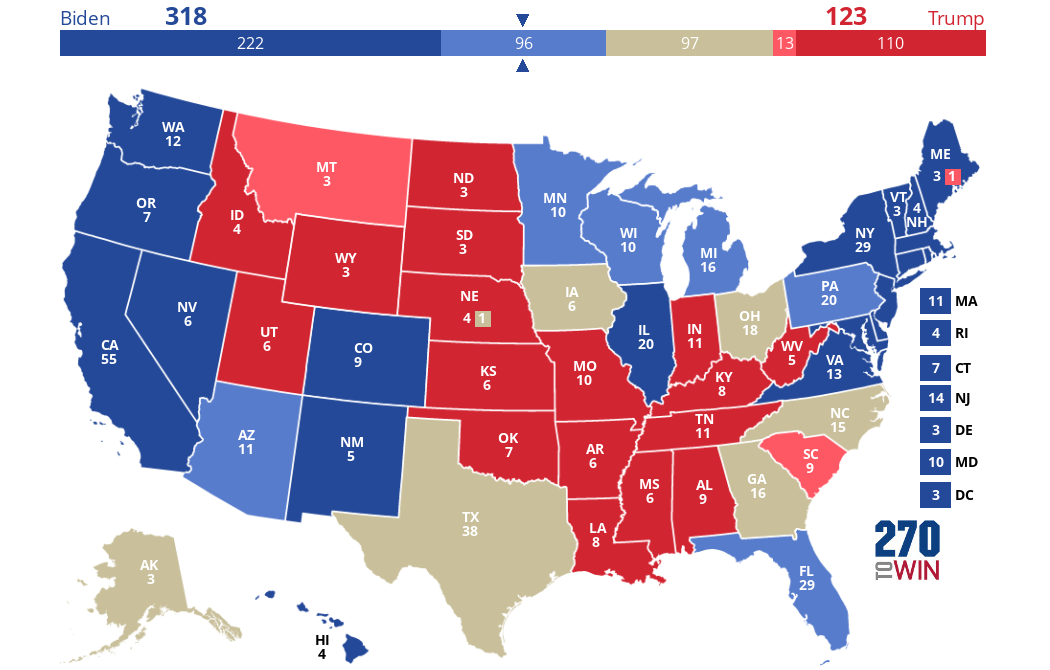

On this year's Presidential election Bitecofer is the only analyst who has offered a firm prediction that Trump will lose. Here is her forecast map of the election, which predicts a Democratic majority in the Electoral College (Note that brown is colour of toss-up states):

But wait I hear you say, isn't Trump gaining ground with his daily press conferences on TV. Well, not so much anymore. Here are the results of a tracking poll asking respondents about his handling of the coronavirus crisis.

The pandemic is hurting Trump not helping him. Thus we see desperation initiatives like suspending all immigration - although that might end up like other Trump moves as no more than a tweet.

I expect Trump to lose.

Click the map to create your own at

Click the map to create your own at